Should we hope the past evaporates?

Reasons for and against hoping that past moments cease to exist

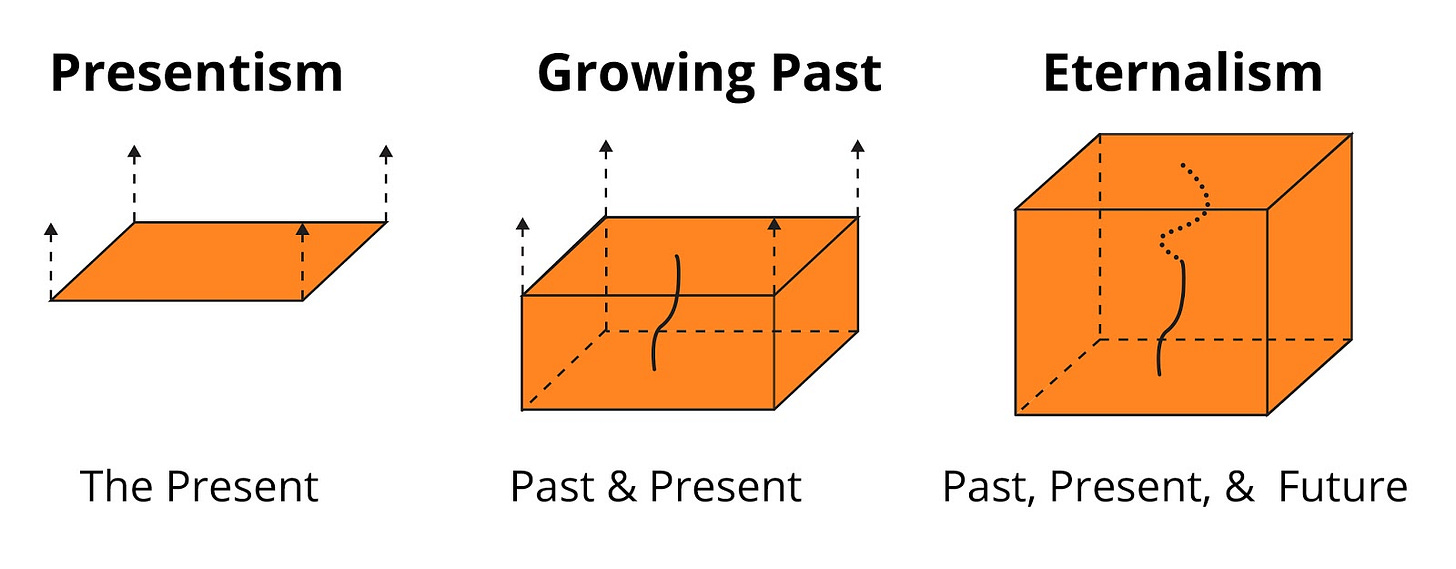

Three metaphysical theories of time

Philosophers have developed several theories of time that situate the present moment in relation to the past and future. There are broadly three theories of time: externalism, growing block (or growing past) theory, and presentism.

Externalism is a theory of time that holds that past, present, and future moments are equally real and banal. What does that mean? Take spatial locations as an example. You are located somewhere reading this article—perhaps in your office on your work computer, on public transportation reading on your phone, and so forth. There is nothing objectively special about the spatial location where you are reading this article—it may be special to you, because you reside there, but there is nothing intrinsically special about the spatial location you occupy.

According to eternalism, that applies to time too: the present moment isn’t any more special than moments in the past and the future. The past, present, and future all exist relative to each other—the present moment we occupy is just as real as past and future moments. There is nothing privileged or special about the present moment, according to eternalism, since it is just as real as past and future moments.

Presentism is a theory of time which posits that only the present moment exists, and that past moments and future moments—they did, and will, exist—do not exist relative to the present (the only existing moment). There are truths about the past that still hold (e.g., John Wilks Boothe killed Abraham Lincoln), but the actual events themselves, located in past moments, no longer exist relative to the present moment. It was (and remains) true that Abraham Lincoln many years ago, but there is no past moment occupied by Mr. Lincoln. The same holds for every past and future moment—the present moment exists to the exclusion of past and of future moments.

The growing block theory is a mashup between eternalism and presentism: while past and present moments are equally real on this view, the future moment isn’t because future moments do not exist relative to the present moment. On some versions of this theory, moments in the past exist and are real, but the present moment is privileged—it isn’t just that one occupies the present moment, but that the present moment is special, and privileged. On other versions of the theory, future moments do not yet exist, and the present moment is no more special than past moments.

Philosophers have long debated the merits of these differing theories of time by doing everything from using elaborate thought experiments, appealing to the physics, and poking holes in each others’ intuitions about time. Put that aside. Here we are focused on a distinct, but related question: should we hope that the past evaporates? If presentism is true, then past truths still hold, but objects and events in the past no longer exist. This is similar to something evaporating, like a puddle, except applied to past moments and everything they contain. Would it better or worse if the past evaporated?

The case for evaporating

Consider that, unlike on eternalism or growing block theory, nothing exists in the past. There are past truths—the United States is a former British colony remains true, even though the past moment in question ceased to exist long ago—but there are no past moments to, in a sense, temporally houses the occupants of those past events. So, for example, if one had a working time machine, in a universe where only the present moment existed, there would be no past moments to travel back to, even though there would be past truths that still obtain. As Steven Hales explains,

For presentists, getting into a time machine is suicide – the occupant goes out of existence. Recall that presentists are committed to a purely objective present; the events and objects at this objective present alone are real, even if other things have been or will be real. After entering the time machine, Dr. Who no longer exists in the objective present, and therefore he is no longer in reality.

The point is not to focus on the alleged suicidal nature of time travel in a presentist universe, but to highlight that, though past truths still hold relative to the present moment, if presentism is true, there are no past moments to which one could travel in a time machine. And this to be expected on presentism.

So if every single thing occupying a moment ceased to exist, when the moment when from being in the present to residing into the past, then that would include occupants of past moments such Adolf Hitler and Genghis Khan—on a presentist view of time, though it would be true, for example, that Hitler invaded Poland, the event ceased to exist the moment is receded into the past. There is no Hitler to invade Poland, and no Genghis Khan to overrun Asia, in the past simply because there are no moments in the past. To the extent that the world—past, present, and future—would be a better place, morally speaking, with fewer people like Hitler or Genghis Khan, it would be better if the past evaporated.

Because there are no past moments, there can be no morally bad past events—though bad events happened, they ceased to exist the moment they receded into the past. And that is overall better from the perspective of aggregating good and bad.

The case against evaporating

There is an upside to the past evaporating: as morally bad events recede into the past, they cease to exist (on a presentist theory of time). However, so do morally good events—the smiles, love, laughter, and happy tears that were once located in the present moment ceased to exist at the moment receded into the past. Presumably, there are many incredibly good, exciting, and uplifting moments that would be lost to the past if presentism happened to be the correct theory of time. Past events—like creating works of art, the discovery of spiritual wisdom and scientific facts—would evaporate as they receded into the past. Each and every one of us, upon our deaths, would cease to exist as the moments we occupied receded into the past.

So do we hope the past evaporates? Or do we not?