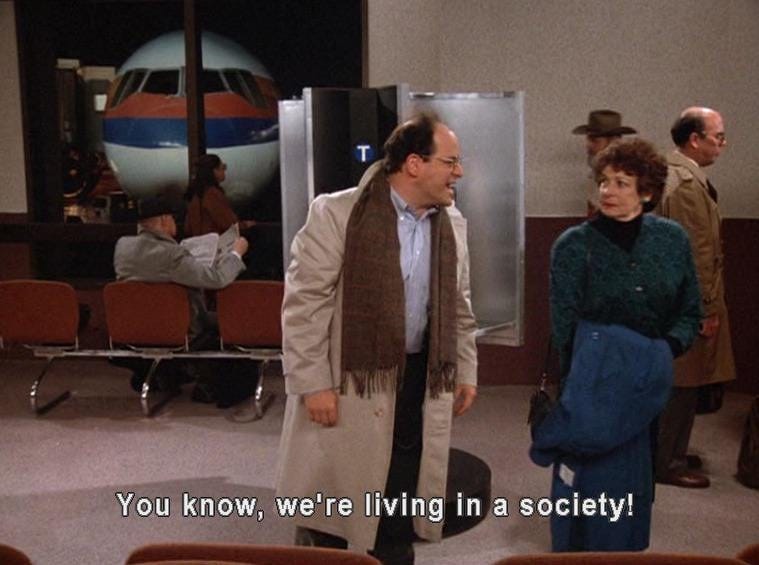

'We're living in a society!'

A Canadian philosopher explains why George Costanza is the GOAT of philosophy, why he would take a Star Trek Teleporter, and more, eh!

Please like, share, comment, and subscribe. It helps grow the newsletter and podcast without a financial contribution on your part. Anything is very much appreciated. And thank you, as always, for reading and listening.

This is written interview with the Canadian philosopher Philippe-Antoine Hoyeck. He teaches at Carleton University. He works on issues in ethics, personal identity, and free will.

JIMMY LICON: You're an academic and philosopher—an unusual and unlikely vocation. How did that happen?

PHILIPPE-ANTOINE HOYECK: I don’t know that I am an academic, actually! I’m not sure what the conditions are for counting as one, but I’m pretty sure I don’t satisfy them. I only have an MA, and while I’m enrolled in a PhD program, I’m currently on a leave of absence and am not entirely sure I’ll finish it. I love philosophy; I love reading it, writing it, and teaching it. But I also have a bit of a love-hate relationship with philosophy as an academic pursuit. Not really sure where that leaves me!

I guess the real question, then, is: How did I end up in philosophy? It was kind of a fluke, honestly. As a teenager, I was really preoccupied with ethical and metaphysical questions—that’ll happen when you have a foot in three different cultures with three different attitudes to ethics, politics, and religion—but I had no idea there was a field dedicated to exploring those questions! I took a philosophy class as an elective in my first year and it was love at first sight.

JL: You work on issues in ethics, political philosophy, and personal identity. Why those topics?

PAH: I was drawn to ethical and political questions from a very young age. Again, when you’re a kid and you live in multiple cultures and the adults from those different cultures disagree sharply about ethics and politics, it’s natural to ask “Hey, wait a minute, they can’t all be right! What’s the truth here? Is there a truth?” These kinds of questions became even more pressing for me when I lost my faith at age fifteen. They became kind of an obsession, really.

In a way, I was intrigued by personal identity pretty early on too, though I didn’t really delve into the philosophical literature on it until a lot more recently. I’ve always been struck by the similarity between my relationship to my future self and my relationship to other people. And that similarity has informed my long-term decision-making since my teens. So I guess the answer to both questions is: I’ve just always been very preoccupied by really weird things!

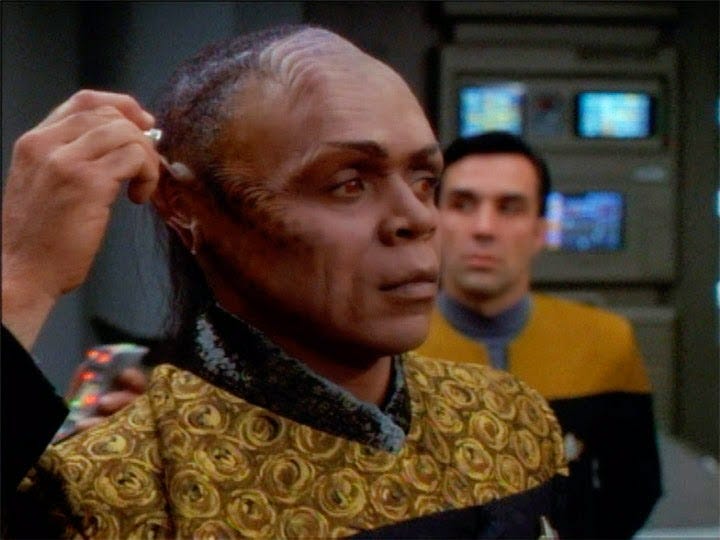

JL: You study personal identity—the question of what makes us who we are. So, would you use the teleporter in Star Trek? Why or why not?

PAH: Yes, I would! Or rather, maybe I should say: I think it’d be perfectly rational for me to use it, even thought I might have some kind of irrational fear about it. I mean, I get the heebie-jeebies just having my blood taken at the doctor’s! Can you imagine how much worse it’d be if I knew I was about to be decomposed into atoms or converted into energy and then built back up like a big flesh Lego set? Gah!

Why do I think it’d be rational to use a Transporter? Well, people’s main concern is that it’d amount to dying. Now this touches on my views on personal identity, but to me, whether it would or wouldn’t count as dying is basically just a question about how we want to use language. It really doesn’t seem like it could matter either way. Suppose I’d been transported without my knowledge ten years ago. Maybe you’d want to say that, strictly speaking, the original Phil Hoyeck died at that point and nobody noticed. Well, okay. But then who cares? It doesn’t make any difference to anyone!

JL: If you had to choose, what’s your favorite theory of personal identity?

PAH: Oh, reductionism about personal identity for sure. I defend a more or less Parfitian, more or less Buddhist view of personal identity. When philosophers ask about personal identity, they’re asking: What makes someone the same person over time? What makes it true, for example, that the guy who played Luke Skywalker in Star Wars back in 1977 is the same guy as the one who played him in The Last Jedi in 2017? What makes them one and the same person?

And the answer I give is: a linguistic convention. Sounds paradoxical, I know! But the idea is that, independently of language, there are only facts about physical events, mental events, and their spatiotemporal relations. What makes it true that the guy who played in Star Wars is the same one as the guy who played in The Last Jedi? Well, that’s just the way our concepts of a person or of an individual work. They group physical and mental events in those kinds of relations.

JL: How do your views on personal identity shape your views on ethics? Can you give a couple examples?

PAH: The two are pretty closely related, actually! I’m not really a full-blown utilitarian, but I do lean toward the view that we should, at least at some abstract level of moral thinking, grant the same weight to everyone’s good. But in that case, there’ll often be a conflict between what morality dictates and what self-interest dictates. So it might seem natural enough to ask: Why should I care as much about people who aren’t me?

If reductionism about personal identity is true, it looks like it might undermine this line of reasoning. We’d usually say that I have good reasons not to now do what’ll harm me in in the future. But if there’s no deep sense in which that guy in the future will be me, it becomes a lot less clear why I should be concerned with his interests over the interests of others. My present self’s relation to my future self is, as I pointed out earlier, not unlike my relation to other people.

As for examples, well, suppose I’m thinking of engaging in some dangerous behaviour but that the only person it could harm is me. You might think this is just my business; I can do whatever I want to myself! But if reductionism is true, this might be no different than engaging in behaviour that could harm someone else. There’s no real reason my present self would be exempt from having to consider the interests of my future self.

JL: Can determinism and free will both be true? Some argue that compatibilism can reconcile the two, while others are skeptical. Where do you stand?

PAH: I defend compatibilism, actually. I think that even if causal determinism were true, it would still be true that we have free will. In a nutshell, I think that, when you look at how we use the concepts of being free to choose or of acting out of our free will in everyday life, you find that what we’re talking about is something like uncoerced voluntary action. That is, we’re talking about actions that we commit on purpose and without coercion.

What’s the upshot here? Well, we can clearly distinguish between actions that are voluntary and unvoluntary, and between actions that are forced and unforced, whether or not causal determinism is true. So it looks to me like determinism is just irrelevant to the question. Everything we care about when we draw the distinction between actions that are freely willed and those that aren’t stays exactly the same whether causal determinism is true or false.

JL: Are social norms and societal rules just tools of control, or do they serve a useful function? What can George Costanza teach us here?

PAH: George Costanza is the greatest philosopher who ever lived and I simply won’t abide anyone saying otherwise. It’s a little-known fact that Costanza was one of the most eloquent defenders of social contract theory. As he puts it: “We are living in a society. We’re supposed to act in a civilized way.” That is, when we live in a society, we have to override our own self-interest and abide by impartial rules.

When you’re an angsty teenager like I was, you tend to ask questions like Is anything really right or wrong? Does anything even matter? The cool thing about social contract theory is that it gives us a way to justify social norms without appealing to anything like objective moral truths that are somehow just “out there”. The idea is that we adopt impartial social rules because, if we all just did what was in our own self-interest instead, it’d be worse for each of us. And this explains the usefulness of these norms. They make each of us better off.

JL: What's the biggest misconception people have about philosophers or philosophy? Why are they wrong?

PAH: I think a lot of people have this mistaken image of philosophy as just consisting in a bunch of bearded men in togas coming up with deep-sounding platitudes and paradoxical questions: “Everything happens for a reason!” “Life is what you make it!” “What’s the sound of one hand clapping?” They don’t know what the activity of philosophy consists in. This is reflected in that ever-grating question, “What’s your philosophy?”

Relatedly, people also have the sense that philosophy has to be cryptic, ambiguous, enigmatic. Now granted, some philosophy is like that—but then it’s just bad philosophy! (Not naming any names, of course). As I see it, good philosophy strives for precision, clarity, and rigour. Much to my students’ dismay, doing philosophy requires you to show your reasoning. And that means defining your terms, specifying the structure of your argument, considering objections to your view, and so on.

JL: Relatedly: what is a philosophical question you think more people should be asking right now?

PAH: I’m honestly not sure about this one. If you’re asking what question philosophers should be asking that they aren’t already, I’m not sure there are any! Virtually every conceivable metaphysical, epistemic, ethical, and political question is being discussed. I mentioned earlier that I have a love-hate relationship with academia. Part of the reason is that I’m just not that interested in research. I tend to think that most of the really important stuff has already been said.

For this reason, I’m much more interested in teaching and in public-facing work. Besides its just being great fun, I think it’s important to familiarize people with philosophy. One reason is that it’s a good way to foster epistemic modesty, which is crucial for a well-functioning society. When you realize how complex these questions can be, I think you probably have less of a tendency to be dogmatic and unreflective in your views. That’s the hope, anyway!

JL: Talk about a time in your life when you failed—professionally or personally—and what it taught you.

PAH: Oh boy. Why would you do this to me? I was having such a good day. Honestly, though, it’s pretty hard to pick just one thing. I guess a common experience of failure I’ve had is that of realizing I was wrong about something. Probably not quite the kind of failure you’re asking about, but a very instructive one, I think, not to mention a humbling one. There’s very little I hate more than being wrong!

As for what that’s taught me: Well, more than anything, to be a lot more cautious! Some people get annoyed at how hesitant I am to take sides in disagreements, especially moral and political ones, but I can’t help it! Experience has taught me that it’s all too easy to get caught up in the heat of the moment and come to the wrong conclusion. I said I was a lot more interested in teaching and in public philosophy than in academia, and this is a big part of why. I think some exposure to philosophy can help us be more careful, more skeptical, thinkers.